Software Lessons Learned From Assembling a 3D Printer

01 Jul 2015 . tech . Comments

#software #hardwareA few weeks ago the Garage team of my office got a little present, an IKEA DIY 3D printer.

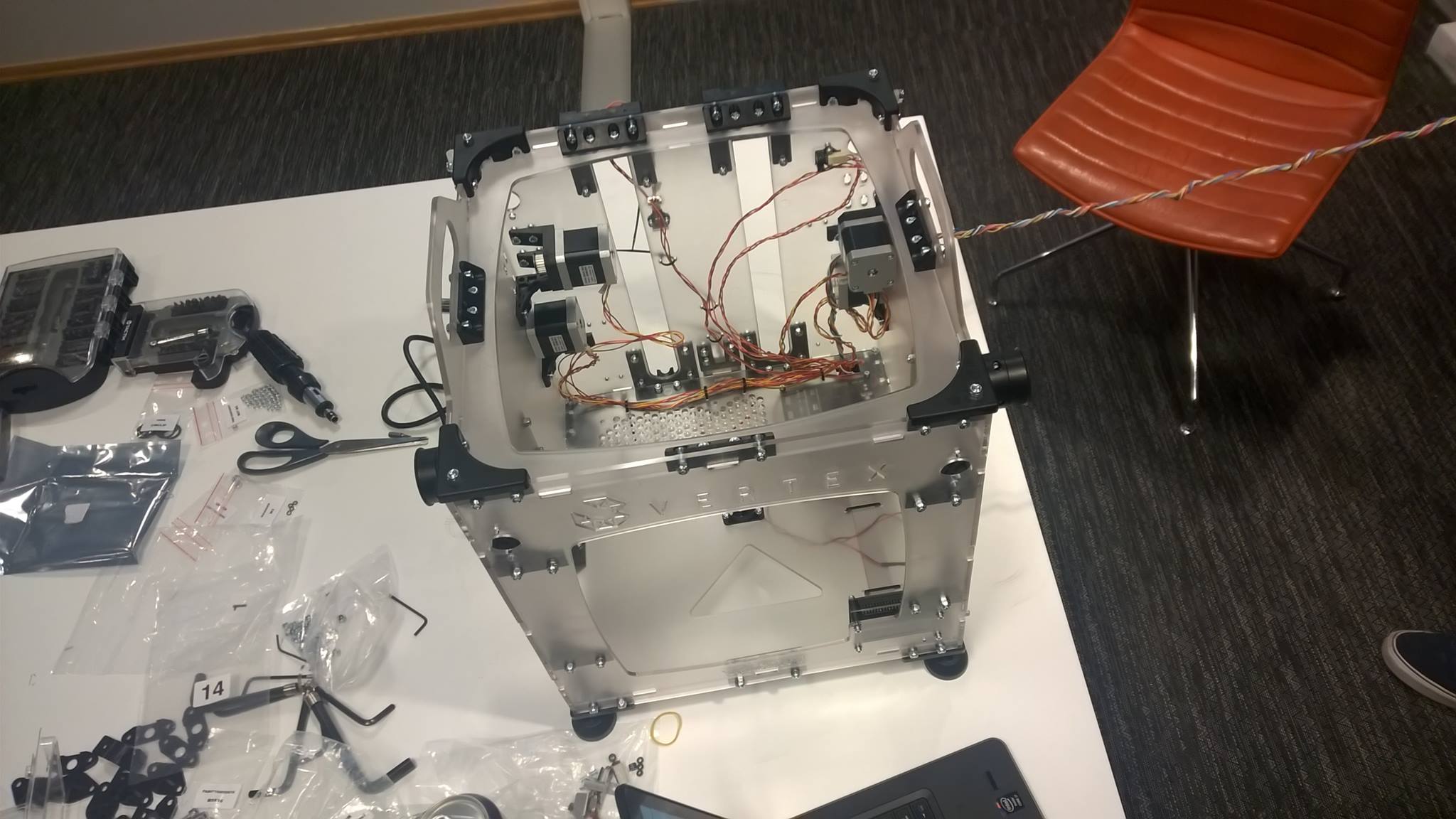

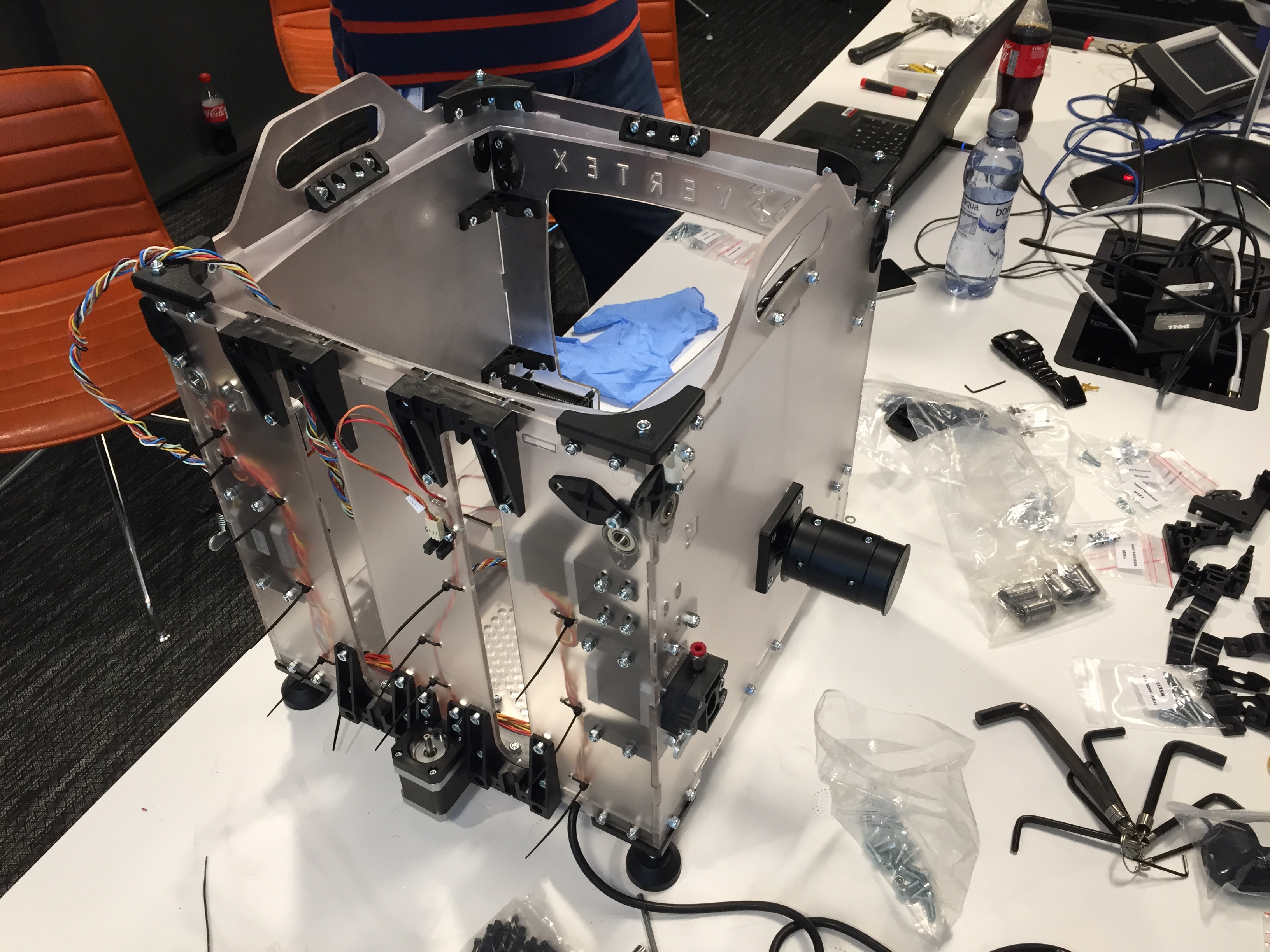

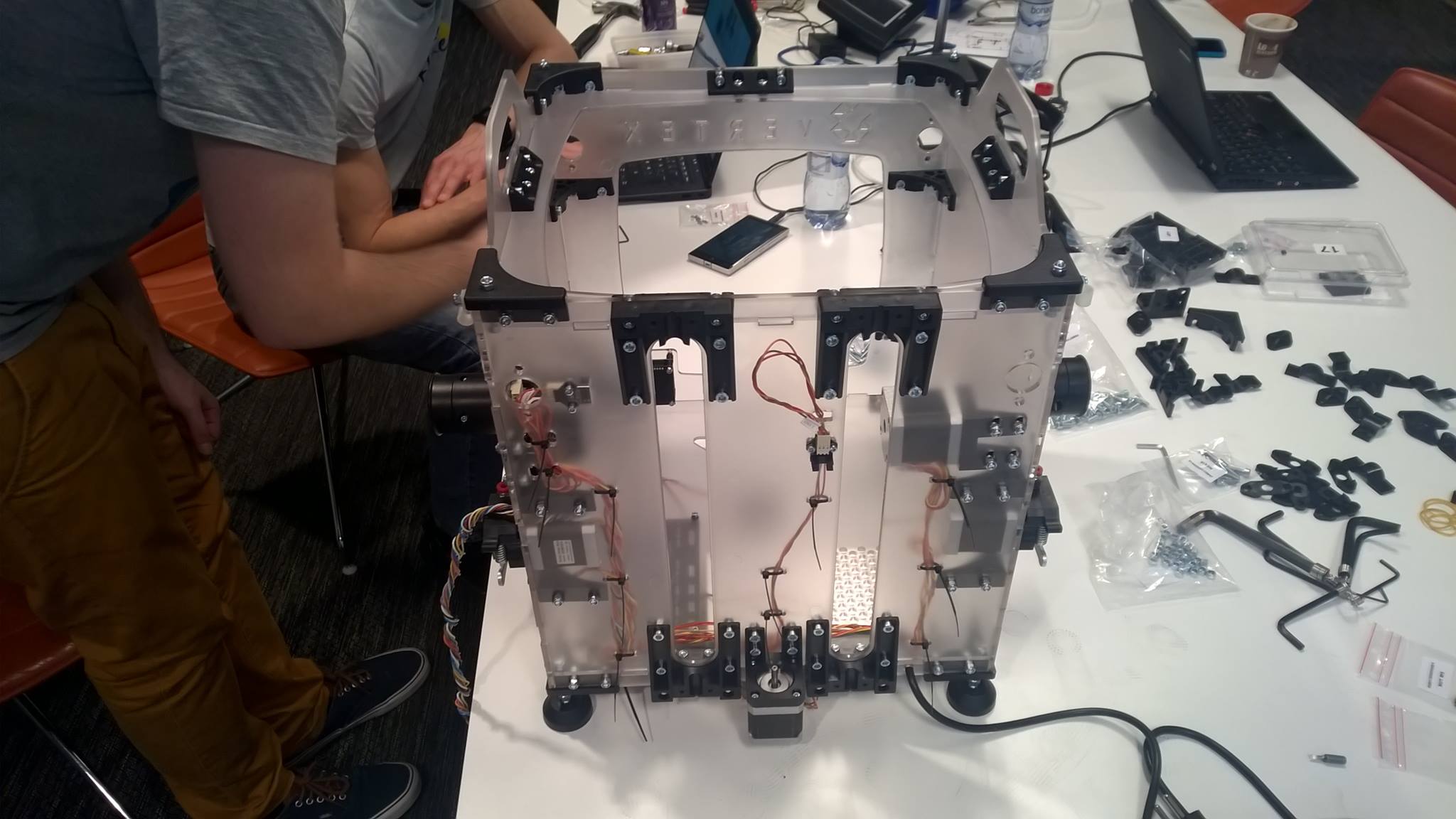

It was zillions of bolts, nuts, wires, motors, rods and tiny plastic pieces which I couldn’t imagine that they could assemble a 3D printer.

I panicked, believing that we will miss a piece and everything will collapse in front of us.

Whenever I have dealt with hardware so far, I was always frightened.

You don’t call methods, you screw bolts, and they have to be screwed properly, not too tight and not too loose.

It’s not uncommon that testing will not be applicable.

You will assemble, hit a big button and if every component works, then you call it a day.

You can’t copy-paste hardware, you don’t have a versioning control system git to undo steps in an instance,

you are on your own and mistakes can literally make your project fall apart.

And on top of these, we shouldn’t touch the rods with bare hands, because they would corrode.

Hardware always made me feel nervous and from the point of creating personal pet-projects,

suddenly I had to collaborate with others in order to build a pyramid.

It was the similar feeling that you get when you start at your first job after finishing your studies.

My panic monster instructed me immediately to sort all the numbered bags per category (bolts, nuts and miscellaneous) in order to access them efficiently.

Like a real life index, which proved to be valuable during the first hours.

We broke down the project into a few independent branches and started following the respective instructions.

These instructions were practically our software spec equivalents in our new hardware world.

They were very detailed and with plenty of images, which made you wish all the software specs to be like these.

Because you knew exactly what you had to do.

As a result, the only way you could introduce a bug, was by missing a step of the instructions or misunderstanding one.

As you can imagine, we missed and misread steps and we realized our mistakes during each individual integration.

Just like in the software world.

The very first mistake that we discovered was when trying to mount the control board on the box.

The bottom side of the box was not placed in the correct orientation, which blocked the card reader of the board.

The result of this?

We spent 45 minutes of unscrewing and screwing more than 60 bolts and nuts.

We made 5 more mistakes, which most of them happened because we were tired (the first session lasted 12.5 hours, following a full working day).

Every one of them cost us time (in the order of half-hours) but also mentally, because we had to take several steps back in order to make one correct step forward.

For the later cost, the most expensive mistake was when just before the end, we realized that 4 nuts were missing from the belt clamps.

In this case we had to unmount the whole printer head in order to fix them and this process took us one more session of 3 hours.

One good habit which prevented us from introducing more bugs was that we code hardware-reviewed each other.

We didn’t keep this safety net during the whole process, it was happening organically when we were taking breaks.

Summarizing, being organized is useful and it will probably prevent a few bugs. Even if you have the perfect spec, you will introduce bugs. The more careful you are, the less bugs you will introduce and the more tired you are, the less careful you become. The bugs will show up during integration. When something fails, we will fix it. It’s not the end of the world, it just takes time and it hurts your motivation. And finally, you need a team, for having fun during the creative process, for agility and as a safety net to each other.

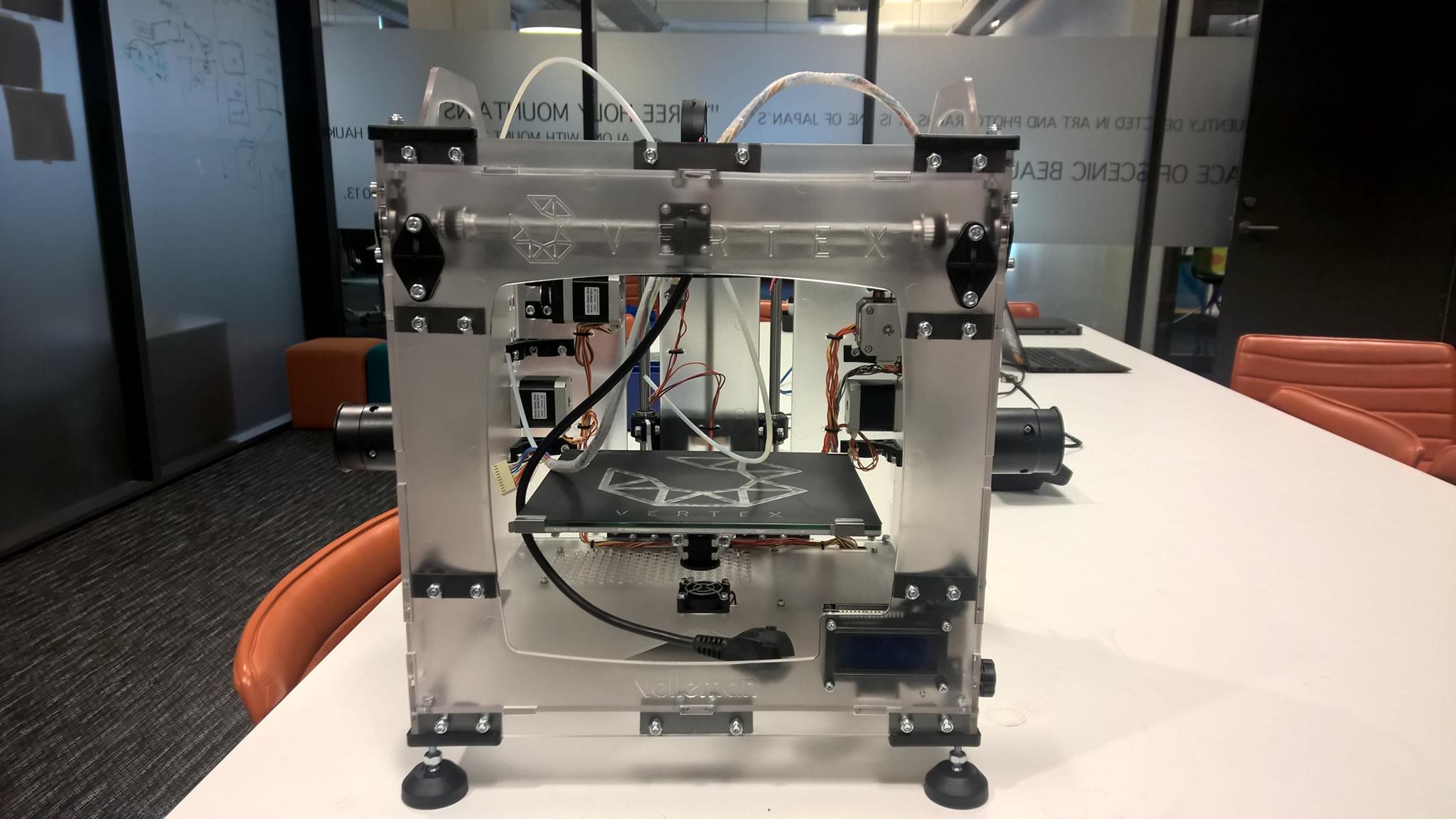

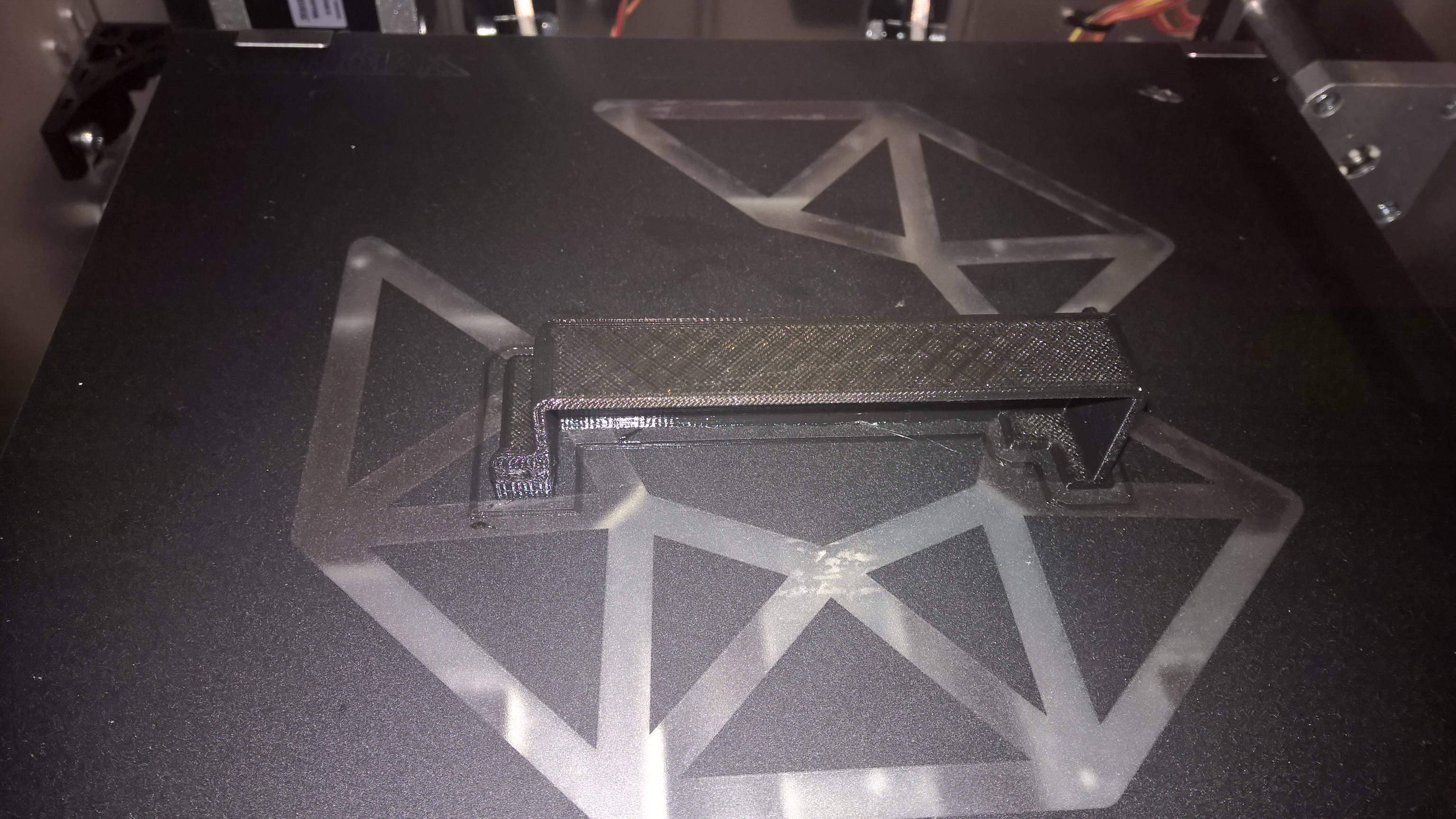

Photos